Invasive devices themselves don’t cause infections, but they can provide a route for bacteria and fungi to enter the body. This can happen in different ways.

During insertion

Healthcare professionals must maintain a sterile field when inserting devices. The equipment must be sterilized and sterility must be maintained during the insertion procedure. If the device is contaminated or becomes contaminated during the procedure, there is the risk of infection.

After insertion

The site or area must be kept as clean as possible after insertion. There is now an unnatural opening into the body that can allow bacteria and fungi to enter. Here are a few examples of how to reduce the risk of infection with some invasive medical devices.

Intravenous lines:

Most facilities have guidelines regarding how frequently to change IV lines and IV sites (where the catheter enters the skin). The most common recommendations are to change IV tubing every three to seven days, unless the patient is receiving blood products or fat emulsions. Tubing for these products need changes within 24 hours. Certain types of medications given by IV also require more frequent changes. While it can be painful to have an IV inserted, the catheter (“needle”) should be removed and the IV restarted in another area every 72 to 96 hours.

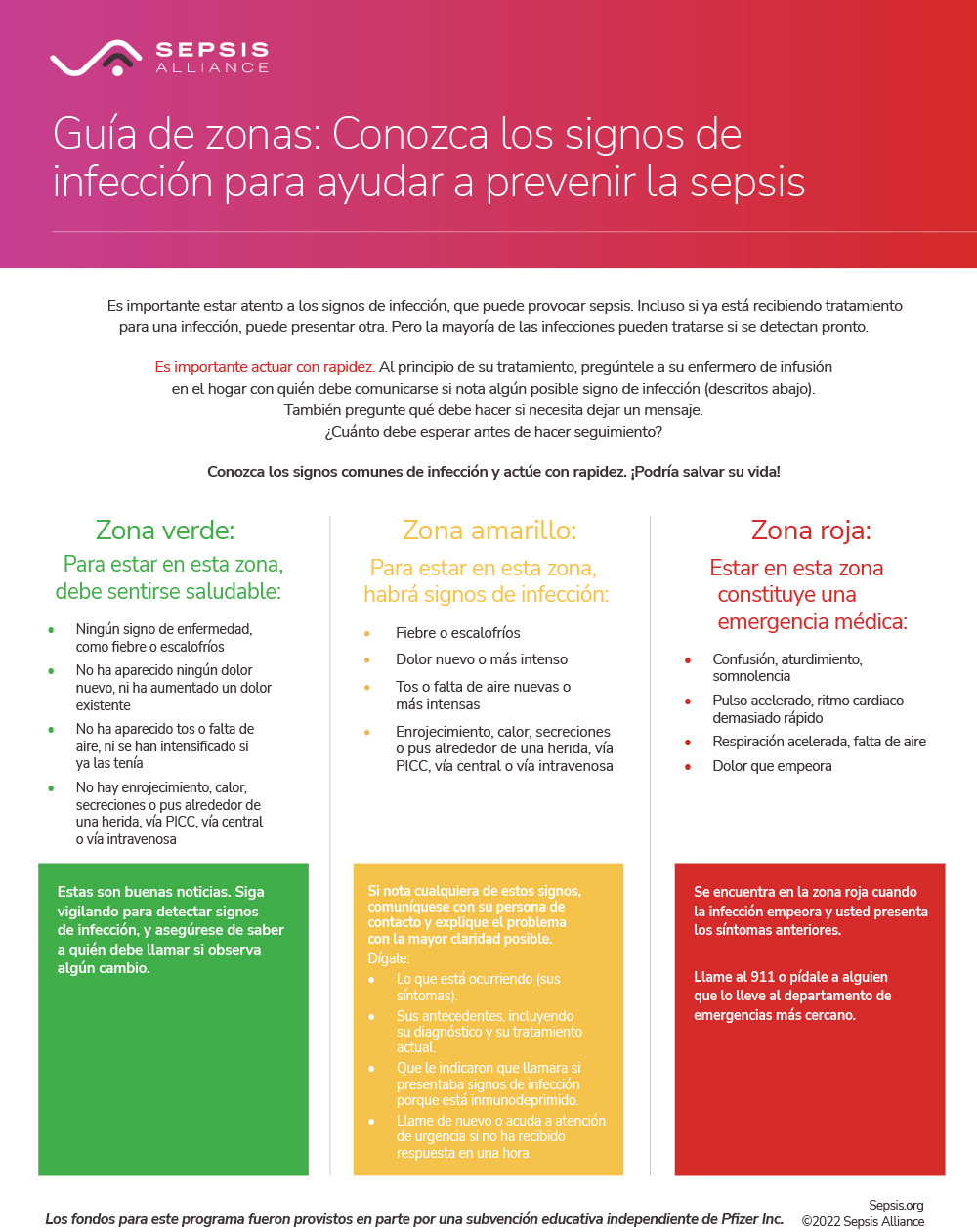

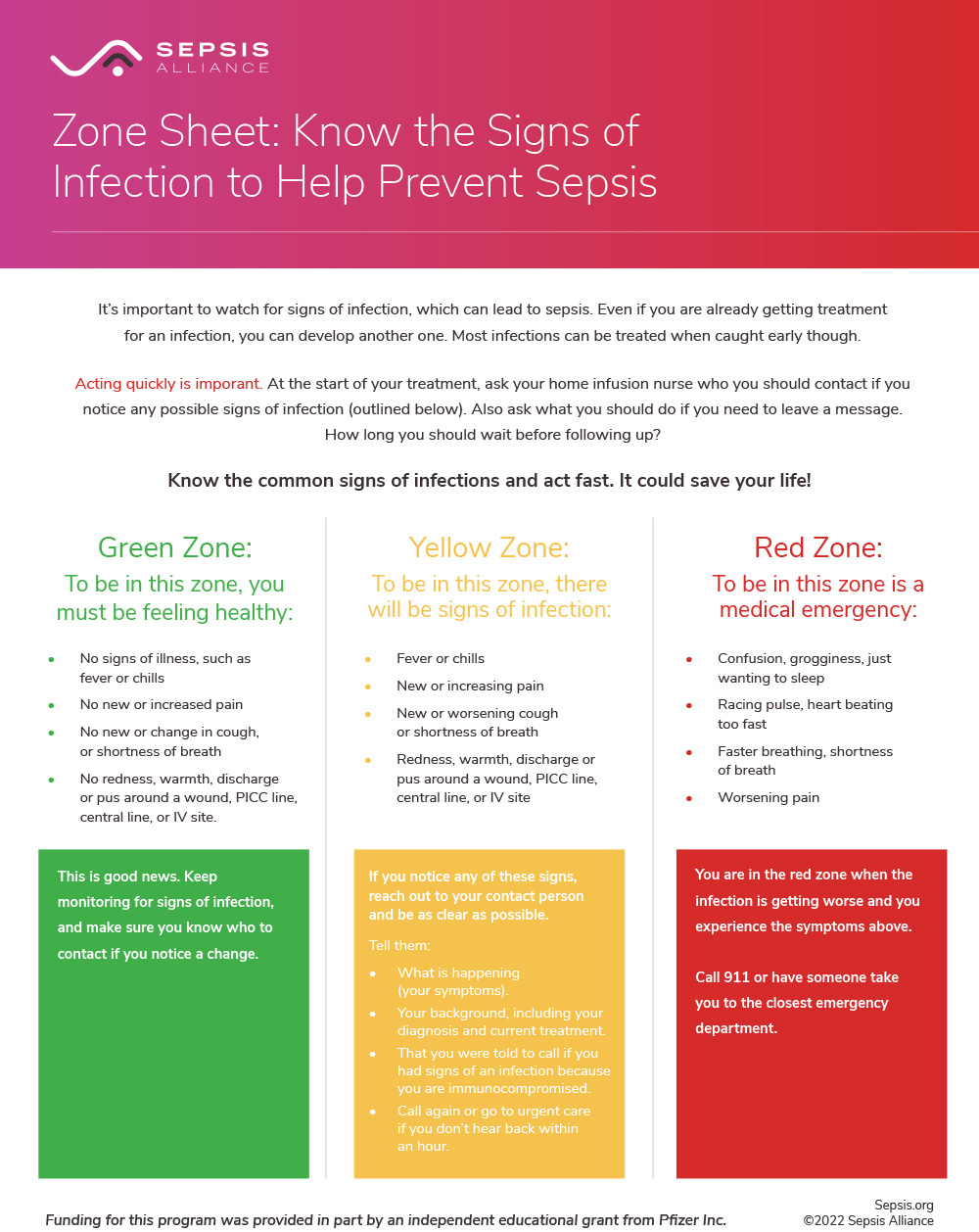

Signs of an infected IV site include redness around the catheter insertion site, pain, and skin that is warm to the touch.

PICC lines and central lines are not replaced at the same rate as IVs. Inserting these devices requires special care with surgical masks, gowns, and sterile gloves. This allows the devices to remain in place for longer, as long as they do not look infected.

Urinary catheters:

People with urinary catheters are at risk for developing urinary tract infections (UTIs). The catheter provides an opening into the bladder for bacteria to enter. Urinary catheters should never be left open to air. They should be attached to a closed-bag system, with the bag positioned lower than the body for urine flow. These should never be placed on the floor though. Bacteria may collect on the bag and then enter the system. The bag should be emptied at least every 8 hours or when it is full, whichever comes first. It is also important that good hygiene be given to the genital area on a regular basis.

Urinary catheters are inserted for a variety of reasons, but are not usually meant to be left in for long periods of time. A person may have a catheter after surgery or if they aren’t urinating. Occasionally, urinary catheters stay in longer than they should. If you have a urinary catheter, you can ask your healthcare professional each day if you still need the catheter.

Signs of a UTI include cloudy and/or foul-smelling urine, pain on urination and fever. Seniors may develop confusion and not show any of the typical signs.

Traction pins:

Traction pins go directly into the bone, so infections could delay bone healing if they develope in the bone itself. Pins are cleaned regularly as per your healthcare professional’s instructions, usually twice a day.

Signs of an infection in the pin area include redness and warmth around the area, swelling, increasing pain at the site, drainage or pus from the site, and fever.

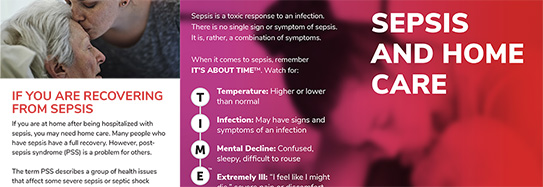

If you have any invasive devices, watch for any signs and symptoms of infection and sepsis.